Urban Green Space: Past, Present, and Future

Turkey’s ongoing developments in Taksim Square in the heart of Istanbul could not be more pertinent to my personal research, but also have important ramifications for all of us and the future of urban design. Two years after the Arab Spring events we are witnessing another similar uprising in a large urban plaza filled with protestors of varying backgrounds seeking potentially disparate outcomes but gathering in the same place nonetheless. The difference with this situation, however, is the root cause of the demonstrations: a top-down redesign of one of the most important green spaces in the city.

Politics of Turkey aside, the privatization of this park was clearly enough for not only an environmental occupation but also the massive gatherings we are still currently witnessing regarding what has been called totalitarian oversight of their daily lives. The fact that a park was the last straw for number of different groups has sparked a discussion once again on what public space (in this case green space) means for the people as an area for refuge and as an agent for change.

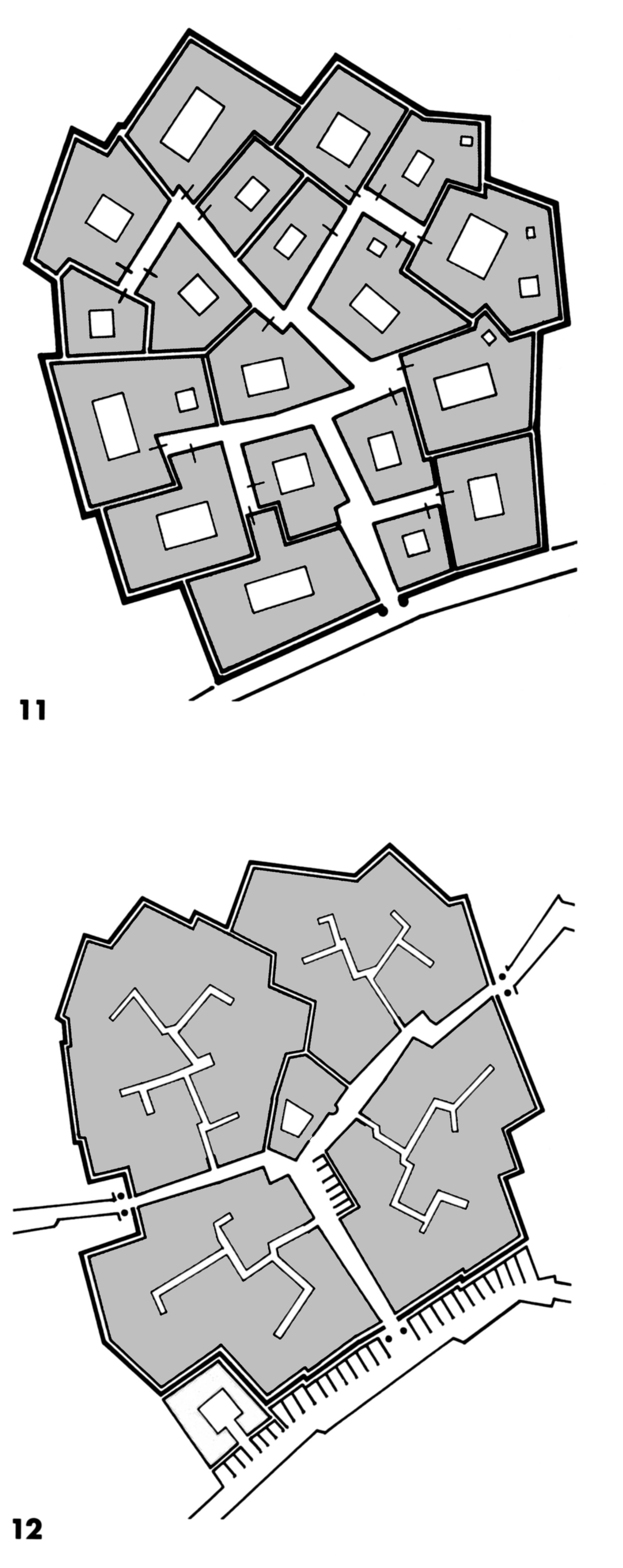

While green spaces are heralded as the mark of a successful city, grassy retreats within the urban boundaries were basically nonexistent in the earliest cities, and even some areas of the world today. One of the earliest known cities excavated so far - Çatalhöyük - is actually in the heart of Turkey, beautifully preserved (comparatively speaking) from around 7500 BCE. This city was more of a compound than anything with no open spaces whatsoever – just a mass of buildings huddled together on a hill. The 5,000 – 10,000 inhabitants moved through the city via the tops of the buildings made accessible by ladders and stairs through holes in the ceilings creating a complex maze of rooms and passageways.

Interestingly, for the most part traditional Islamic cities deviated only somewhat from this original design. Green space within these cities is typically sparse and the emphasis is instead on the streets (they eventually added) as the catch-all public space. Walled compounds surround distinct neighborhood units that were even closed off at night isolating their individual urban alleys (like more verticle and compact cul-du-sacs). Mediterranean cities, too, opted for an emphasis on streets but add the Italian staple, the piazza, to its public space repertoire – spaces still otherwise devoid of green space.

Fast forward a bit, and eventually green spaces emerge around the globe in the form of private and semi-private gardens, foraging and grazing grounds in England, or in the form of hunting lands (massive areas reserved for the leader’s sport). But the stereotypical “park” which we have all come to enjoy was really still an anomaly until around the Victorian era. What began as “promenades” to meander among the social elite in sometimes very strange (read: gender bending) ways, eventually became a desirable space for the common man. Cities like New York preserved semi-natural areas inside their borders like Central Park and the Olmsted era of fresh air really kicked off the park-frenzy, especially in the U.S.

Since that time, the role of green space in cities has seen its ups and downs in various ways. In the case of public housing, a simple green square within the otherwise crowded complex of apartments was believed to increase the health and wellbeing of the poor population. Advocates of this social improvement through design claimed that providing this amenity would decrease crime and provide a space for children to play and avoid the otherwise dangerous inner city environment. The fact that this did not work (generally speaking) is important to consider – it is clear that a park does not a safe space make. In reality, it may be the case that green space without very strict maintenance and even possibly programming, can create a more negative environment. Whyte spoke of this when he helped redesign Bryant park changing it from one of the most crime-ridden green spaces in NYC to one of the most celebrated today – through better design of the space.

So, in general, design seems to be win-some and lose-some depending on the situation (as is always the case). But for some people the creation and accessibility of green spaces was not only done to increase livability on a local scale but to improve their entire country’s population. In the 1930s, during a time of extremely low birth rates in Sweden, planners, led by a husband/wife duo consisting of a child psychologist and economist, created what is now known as the “Swedish Model”. Not only did they provide social welfare on a massive scale, but they also prioritized adding parks to their cities and encouraged adults to spend time outdoors and increase their leisure time (maybe have a few kids…you know...). A similar change also happened in Denmark whereas what was once considered a culture that would never eat at cafes outside or stroll down a pedestrian street is now infamous for their Strøget and street life. For decades these Nordic countries carried the highest levels of happiness, starting at a young age with excellent childcare, maternity leaves, and an emphasis on hobbies and free time with their budding next generation.

Right before the uprising in Turkey, however, Sweden also had its own series of riots spurring from the immigrant neighborhoods that otherwise have a really nice assortment of green spaces to spend (a little too much?) leisure time in. Articles on this odd event for the happy country have picked up on this issue of green space design and its lack of positive effect on disgruntled youth. Is this an issue of design not having the desired effect on social welfare (like our own public housing in the 60s)? The overall state of the global economy is still reeling from the recession, and indeed Scandinavia generally has not been exempt from this. It could also be an issue of culture and indeed the immigrants there (as elsewhere) have expressed their difficulties with merging with an otherwise fairly homogenous culture (though 15% of Sweden’s population are immigrants, mostly refugees increasingly from Syria).

The intersection between what is a protest in Turkey against top-down regulations, and a top-down creation of green space creating a happier culture in Sweden lies in the dichotomy of the outcomes, I think. Sweden may be experiencing a lack of contentment on the part of recent immigrants despite the benefits they receive, including the green space they have nearby, and they are doing so via riots. But also, Turkey may be experiencing a cultural revolution born out of the attempt of their government to create a more “modernized” public space without the consent of their people. What Sweden did in the ‘30’s was essentially social engineering for a positive cause – a sweeping alteration of the culture purposefully done to improve the wellbeing of Swedes with success. Turkey's recent attempt at altering the built environment has instead been met with massive bottom-up resistance as the people themselves want to take the design of their city – and their culture – into their own hands in order to better their own lives. Both involve top-down initiatives in different time periods surrounding public green space, but while one has potentially succeeded and recently failed (or is being criticized) decades later, the other may not even get to experiment at all if the people have anything to do with it.

What we may be witnessing is the birth of a new era – a contemporary culture that wants to take control of their environment, which will no longer allow a government to redesign the city – their city – without their consent. The Right to the City was heralded in the Occupy Movement for their use of public space to protest their grievances and evictions were seen as stifling the right to gather as such. However, The Right to the Entire City may actually be more important to urban design in the future; if you want to design something, you might want to talk to the People first.

For more on these topics:

On green space globally: Gardens, City Life, and Culture: A World Tour (2008)

Within the same book: "Swedish Mid-Century Utopia: Park Design as a Tool for Social Improvements", T. Andersson

On public housing: The Pruitt-Igoe Myth - a documentary on public housing of the same name in St. Louis